The Duty to Remember: Visiting Sainlez, Belgium, a Village in the Belgian Ardennes that was Occupied by Nazi German Soldiers During WWII, and Took Heavy Casualties in the Fight for Liberation. Includes a Visit to Museum Sainlez and La Mémoire Civile, 1940-1945

Disclosure: We took this tour on part of a media trip organized by Liberation Route Europe, and received the experience free of charge. Please note this website also contains affiliate links. That means we earn a commission when you use the links on this site to book a hotel, buy your travel insurance, etc.. You don’t pay anything extra, and it helps us cover our costs. If you’d like to learn more about how this works, you can read more under our Disclaimer page.

Seeing this, and hearing these stories, maybe you can understand why it’s so important for us, Jean-Paul tells us in French, pausing for Martin to relay the message in English.

We’re in Sainlez, a tiny village in the Belgian Ardennes, where, if you blinked while driving through, you’d risk missing a good chunk of what’s here: a single road winding through the village; low-rise houses from the 1950s; and rolling green farmland all the way to Luxembourg.

Despite Sainlez’ diminutive size, it’s a place with a big story to tell, a lesson buried beneath what at first appears to be mundane.

At the tail-end of 1944, Sainlez was occupied by the Nazis. Having let out a collective sigh of relief in early September when this part of Belgium was liberated by Allied forces, villagers were devastated when news broke the Nazis were coming back, due to reach the village with little warning.

In the dead of a bitterly cold winter, days before Christmas, and when the names of those who’d been in the Belgian resistance were widely known, Sainlézienes were forced to come to terms with an unavoidable tsunami of Nazi soldiers and Gestapo hurling toward their village.

Again.

Jean-Paul walks us toward a small stone building, the only one in Sainlez that exists from before the war, and opens a door to reveal a tiny, one-room museum.

The only thing left now are the memories.

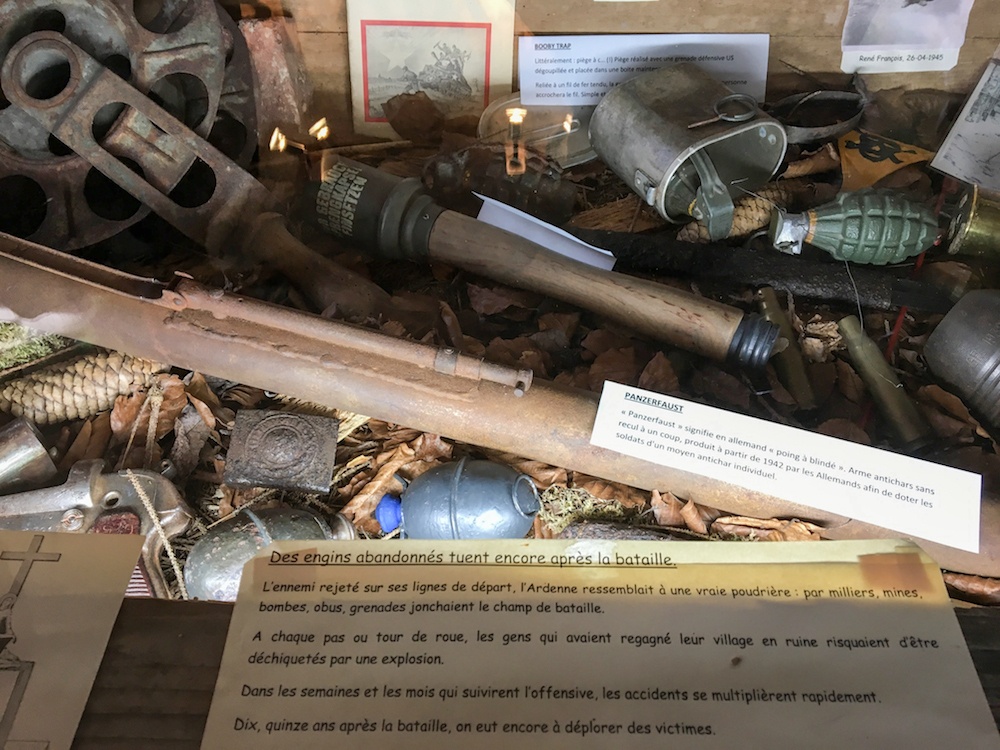

Museum Sainlez, 1944 to 1945, is jammed full of artifacts. Photographs, ammunition, and everyday objects line the display cases. Dioramas of soldiers and villagers stand in corners, modelling scenes of what life would have been like that winter.

Our group of 10 can barely fit in the museum without falling over each other, it’s that small. We begin to wander and ask questions, and our Jean-Paul points out the most interesting parts.

Christmas trees weren’t a tradition in the Ardennes until after the war, he explains, pointing to a diorama of German soldiers celebrating Christmas at a table strewn with bottles, egg shells, and candles, a Christmas tree standing at the far edge.

At another display; The cellars became the only safe place during the shelling…but they could also quickly become a tomb for those hidden below.

Which brings us to the heart of the lesson we’re about to learn: liberation, it’s a messy business.

If you’d asked me describe what the liberation of Europe looked like before we visited Sainlez, I probably would have come up with something like this account of the liberation of Paris (adapted and paraphrased below):

Scenes of jubilant celebration erupted in Paris today, with Parisiens welcoming the liberators with open arms and open beds. Locals cheering the Allies’ arrival in the city halted the soldiers’ advance with displays of unabashed gratitude, as mothers held up their babies to be kissed, old men lined up to shake their hands, flags waved, and champagne corks popped across the city.

Pretty girls kissing soldiers; soldiers handing out treats to children; lots of flag waving…that’s what liberation looks like…isn’t it?

Not in Sainlez, it didn’t.

When you retake a village, it’s a war zone, Jean-Paul tells us.

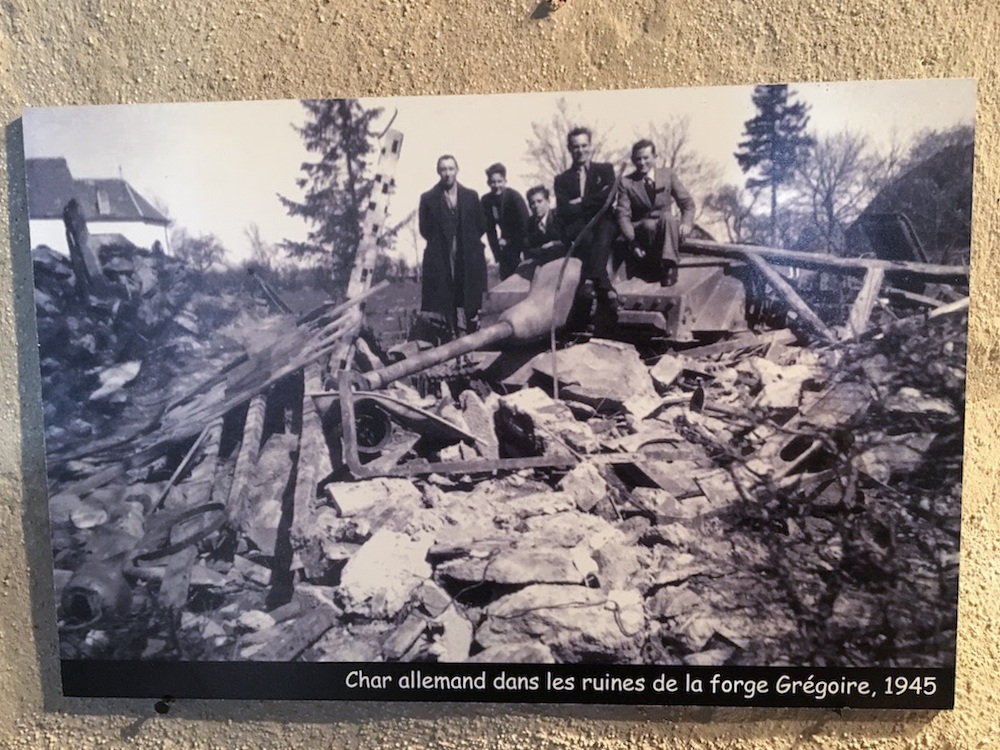

On Christmas Eve, 1944, the Americans began their campaign to force the Germans out of Sainlez, beginning with an all-out bombardment of the village. Whatever wasn’t destroyed immediately upon impact, burned in the aftermath. Almost everything was destroyed.

When the Americans arrived to retake the village three days later, on December 27, they were met by a shell-shocked population grieving the death of 20 villagers. A massive loss from a tiny population.

Far from the baby-kissing and the champagne-swilling I’d always associated with Europe’s liberation, the Americans arrived in Sainlez as scared of the villagers as they were the Germans, not knowing who was who, and managing the uncertainty the only way they knew how: with aggression and violence.

When the villagers were finally separated from the Nazi soldiers — expelled from Sainlez for the final time — the refugee crisis began, as people from roughly 200 villages throughout the Ardennes found their homes and villages either gone or unfit to inhabit.

Drive through Sainlez today, and it’d be easy enough to miss all that happened here. A gently curving road, pastoral farmland stretching in every direction, and those low-rise stucco buildings…at first glance, there’s nothing that gives any indication of the past.

Turns out, that was by design. As villages were rebuilt, the decision was made to stucco over the scars of the past; to cover up the pain of remembering.

Now, though, the village has decided it’s time to change that.

They’ve gotten together to create La Mémoire Civile 1940-1945, 3.5-km route around the village that features eight information panels explaining Sainlez’ experience of the war (currently in French, only). And then, of course, there’s the tiny museum packed full of the villagers’ passion for remembering, Museum Sainlez, 1944 to 1945.

Our visit to the museum ends with shots of fruity gin so sweet, it tastes like something from a kid’s juice box. As the shots are distributed, Jean-Paul sums up his thoughts.

What happened here was a burden the people of Sainlez — even to this day — hold on to.

We must pass it down to future generations. This is the duty of memory.

As we drink our gin, the group falls quiet, and I wonder about that phrase — the duty of memory — as we shuffle out of the tiny museum, and get ready to leave Sainlez.

Walking away, I can’t help but think of what happened 158 km northwest of Sainlez, little more than a year ago.

When news of the Brussels bombings broke, the world reacted with the horrified shock that comes with something so violent, and so unexpected.

That horrified shock is a testament to how far Europe has come in the 72 years since December 1944, when the Belgian villagers who lived here in Sainlez hid as the rolling green hills of the Ardennes transformed into hell.

But it’s also a warning. A mere 70 years ago, Sainlez — this tiny, peaceful, speck of a village in a place so sweetly pastoral, it could make your teeth hurt — was a war zone.

And there’s not all that much from stopping Europe from becoming one again.

That, I realize, is the duty of memory.

Practical Info to Plan Your WWII Bastogne Tours

Sainlez is close to Bastogne, a great place to base yourself on a Battle of the Bulge or WWII-themed trip to the Ardennes. We visited Sainlez as part of a WWII Jeep Tour with Ardennes White Star, but it’s possible to visit on your own as well. The 3.5 km ‘Remembrance itinerary’ walk around the village is open all the time – nothing special required, although it’s worth noting, the panels are currently in French only. The Museum Sainlez is open 10am to 6pm on Saturday and Sunday if you want to visit on your own, although we highly recommend getting in touch with Ardennes White Star as well, via their website.

If you go, there’s a lot in the area to keep you busy. The Bastogne War Museum, opened in 2014, is excellent, and sites in nearby Luxembourg offer a more complete story of the Battle of the Bulge: Ettelbruck, known for the General Patton Museum; Diekirch, home to Luxembourg’s National Military Museum; Clerveaux, a site of fighting during the Battle of the Bulge; and the Luxembourg American Cemetery in Hamm, where Patton is buried.

We visited Bastogne as part of a media trip with Liberation Route Europe, a not-for-profit dedicated to creating an international remembrance trail that connects important sites along the Western Allies’ advance across Europe. If you’re planning a WWII battlefield or remembrance trip, we’d recommend checking out the Liberation Route Europe website and several free apps they offer.

If you choose to stay in Bastogne as a base, Nuts Castle has a historical connection, as it served as the US 101st Airborne’s Headquarters during the Battle of the Bulge. If you’d rather stay in a hotel, Hotel Melba and Le Merceny are both highly rated.

What do you think about our experience visiting Sainlez? Are you planning a Battle of the Bulge or remembrance trip?

Like This Post? Be Sure to Pin it for Later!